For all the title’s alignment of ‘Island’ and ‘Ireland’ Heaney presents his four-piece sequence of 1985 as a fictional place in which he is a silent listener. The clues he feeds into the narrative reveal, however, that he is on home ground.

Helen Vendler’s view that the importance of these poems of competing discourses lies in the poet’s conviction that the person who owns the language owns the story, and that he who wishes to change the story must first change the language (HV125) is at the very source.

Parable Island regrets the seeming impossibility of what Heaney yearns for in his every sinew: he senses that from the way they communicate with each other the Irish themselves have placed his notion of integrated nationhood beyond reach.

I

Parable island is a divided place: non-Irish invaders (occupied nation) and much more recent trade-offs brought about by sectarian confrontation (their only border is an inland one) have blocked geographical unity. The wagging finger of his concessive ‘although’ warns, however, that the Irish race is, as one, emotionally uncompromising (yield to nobody) in its belief of undivided Irishness (the country is an island).

Heaney homes in on the northern sector with the precision of a satellite zoom … from somewhere in the far north to a region with a popular label (‘the coast’), then via a geological clue to Co Antrim’s North Coast (Cape Basalt) coming finally to rest on breast-shaped Aird Snout overlooking the Giant’s Causeway itself.

Enter language: the feature bears other labels: known to generations of local farmers in the east as the Sun’s Headstone (after all the sun sinks behind it at the end of each day) and, because of its breast-like shape, given a vulgar nicknamed by incomers (Orphan’s Tit).

There is no unity (mountain of the shifting names) so who might have wished to change the island’s story failed to change the language first.

Political division has led to cultural distancing: local attitudes are ‘uncharted’ (no map) – remaining alert to language is paramount (keep listening) – the traveller will sense if he is accepted or acceptable on either the one or the other side of the frontier (the line he knows he must have crossed). In the later ‘Wolfe Tone’ poem not listening is precisely what brings the man down.

Heaney can see the impasse: the Irish say one thing and believe another (forked-tongued natives), half believing the superstitious promise (prophecies they pretend not to believe) of some legendary cavern where a common language lies dormant (all the names converge) in which, who knows (some day), his countrymen may come to recognise the richness of shared heritage (start to mine the ore of truth).

- occupied: under foreign control

- border: geographically and politically the partition of Ireland(Irish: críochdheighilt na hÉireann) of May 3rd, 1921divided the island of Ireland into two separate entities. The smaller of the two, named Northern Ireland was provided with a devolved administration and remains part of the United Kingdom as we speak. The larger territory, intended as a home-rule jurisdiction to be known as Southern Ireland was not accepted as such; it became an independent sovereign state initially known as the Irish Free State, now described as the Republic of Ireland;

- yield: give in to

- Cape Basalt/ Sun’s Headstone/ orphan’s Tit: alternative names for the same mountain, depending on whom the observer is;

- basalt: very hard rock restricted in Ireland to Co Antrim;

- tit: slang a woman’s breast; an animal’s teats for suckling its young;

- cross the line: in one sense cross a border or divide, in a second sense do something that infringes the acceptable;

- speak with forked-tongue: say one thing and mean another; hints of hypocrisy, duplicity;

- mine: extract;

- ore: sediment containing desired minerals e.g. gold;

- 5 verses (V) of different lengths; 7 sentence construct; line length predominantly 10 syllables; unrhymed; plentiful enjambment

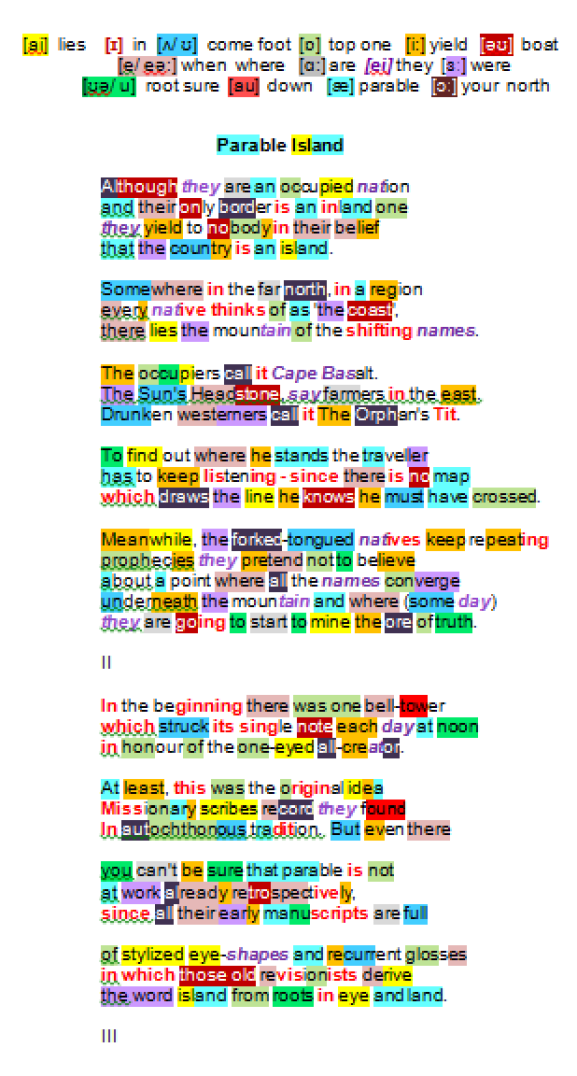

- assonant effects: V1/2/3 [ai] occupied…island; [əʊ] only…nobody…coast…Headstone; [ei] nation…native… names…Basalt; [i:] belief…region; V4/5[æ]stands…traveller……map; [i:] mean…keep…repeat…pretend… prophecies..believe; [ai] line…meanwhile…mine; [ei] natives…names…day;

- alliterative chains: V1/2/3 bilabial [p/b], nasals [n/m], sibilants [s/z/sh]; alveolar [t/d]; V4/5 labio-dental [f/v], sibilant [z]; nasals [m/n]

II

Heaney reflects on images of the earliest Celts (In the beginning) and the uncanny ‘parable island‘ resemblances with what has followed. The piece hints at control and controlled, not least Church and people.

The earliest Christians reported a bare Celtic landscape: its single solitary fortified column (one bell-tower); its regulated monotone church bell calling people to duty (single note each day at noon); its worship of a narrow-minded deity (one-eyed all-creator).

Such were the words of those historical incomers tasked both with converting paganism and copying manuscripts – missionary scribes describing a limited indigenous population sprung from the land where it evolved (autochthonous tradition).

Heaney cannot escape the sense (you can’t be sure) that the imposition of power and influence involved some distortion of the past (stylised): things staring into the soul (eye-shapes); the elbow-jogging reminders(recurrent glosses) of propagandist spin (old revisionists) betraying their lack of depth by their spurious derivations (the word island from roots in eye and land).

- missionary scribes: clerics sent form the earliest Christian settlements to convert the ‘heathens’; they also copied existing manuscripts for posterity;

- autochthonous; describing a population indigenous rather than descended from migrants or colonists;

- stylized: presented in a mannered, non-realistic form:

- revisionist: person with a vested interest in re-interpreting existing facts;

- gloss: note figuring in the margins or between the lines of books being read, not just as a personal comment, explanation, interpretation or paraphrase but equally a new layer of consciousness or a fresh association to be borne in mind ;

- root: original linguistic starting point;

- 4 triplets (T) in 3 sentences; heavily enjambed; predominantly 10 syllables; unrhymed

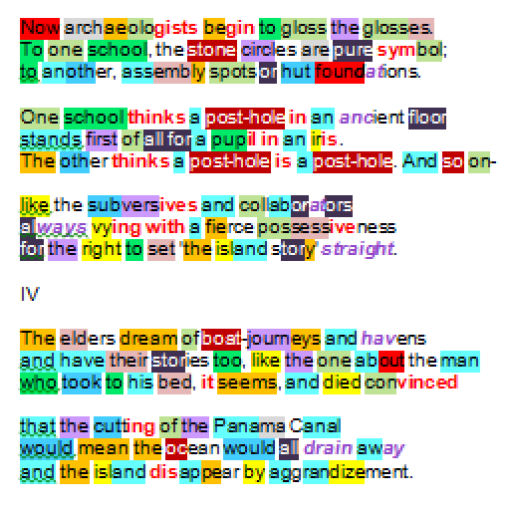

- assonant effects: [ɒ]one…honour…one-eyed…was…autochtonous; [i] beginning…which…its single……this…missionary…tradition…retrospective…script; [ai] idea…scribes…stylised.. eye-shapes…derive…island

- alliterative chains: sibilants [s/z/sh], nasals m/n, alveolar [t/d], labio-dental [v], velar [k/g], bilabial [p/b]

III

Three triplets dwell on the uses to which language can be put either simple concrete/ abstract interpretation or the more insidious means by which power mongers, political, religious or both, justify their ends.

Language can be manipulated to fit the circumstances (gloss the glosses): Irish archaeological features of pre-history (stone circles) are variously defined (according to who you are) as an abstract figure of speech (pure symbol) or something real, historical and community based (assembly spots or hut foundations); a second remnant (post-hole in an ancient floor) is regarded by some as a visual metaphor (pupil in an iris) and by others, materially, as plotting the layout of a former structure (a post-hole). Not in these cases such a big deal, suggests the poet (and so on).

Suddenly Heaney ups the ante, turning his venom on those who appropriate language to disturb the social balance (subversives) or sell their souls (collaborators) to individuals grappling with each other (vying with a fierce possessiveness) by claiming they alone are best qualified to impose their version of the truth (the right to set ‘the island story’ straight).

- archaeology: study of history and pre-history via excavation and analysis of artefacts;

- stone circles: prehistoric stones of which close to 200 exist on the island of Ireland;

- school: body of opinion;

- pupil/ iris: parts of the eye; the circular central opening and the coloured membrane behind it;

- subversive: disruptive opponent of an existing system;

- collaborator: activist, possibly treacherous:

- set straight: provide a purportedly true version of;

- 3 triplets; variable line length 11-14 syllables; unrhymed

- 6 sentence construct with semi-colon – dominated by punctuated phrases;

- assonant effects: [ɒ] archaeologists…gloss…glosses…one…spots…collaborators…possessive; [əʊ] stone…post-hole…post-hole…post-hole…so; [ai] vying…right; [u] pure…pupil; [ei] collaborator…straight

- alliterative chains: alveolar [l], velar [k/g], nasals [m/n], sibilant variants [s/z/sh], alveolar [d/t], front of mouth fricatives [f/v]

IV

Irish jokes are brilliant at exposing absurdity and Heaney finds a tale that turns geriatric ramblings and entrenched opinion (elders dreaming of boat journeys and havens) into parody.

He tells the one about the backward comic ‘feller’ who fell ill (took to his bed) and died still clinging to his opposition to the cutting of the Panama Canal on the grounds that the waters of the Atlantic would drain away into the Pacific! Were that possible it would leave behind a preposterous paradox, says the poet – little Ireland enhanced since it is now part of a huge muddy land mass (island disappear by aggrandizement). Fade out to sounds of mirth!

- elder: senior figure of tribe or group;

- haven: place of safety, refuge;

- ‘the one about’ … stereotypical first line of an unmistakably Irish tale

- cut: extract earth and rocks for a purpose:

- aggrandizement: make bigger; enhance beyond what is justified;

Beyond parable it seems worth adding that he conflict between the largely Catholic nationalists fighting for a united Ireland and the largely protestant unionists in Northern Ireland has boiled up repeatedly over time without ever being settled. Most recently Irish and British governments signed up to the 1998 Belfast Agreement which stated that the status of Northern would not change without the consent of the majority of its population thereby ensuring that dreams of religious, cultural and traditional alignment remain distant.

- 2 triplets in a single enjambed sentence of variable line length 10-13 syllables; unrhymed

- assonant effects: [i:] dream…journeys…seems…mean; [ei] havens…drain away; [æ] Panama Canal…aggrandizement

- alliterative chains: alveolar [d/t], nasals [m/n], velar [k], sibilants [s/z]

Source views

- NC: ‘Parable Island’ the fictional island becomes a text which is differently interpreted depending on the ideological preconceptions of those who study it; and ‘island’ of course is a near-homonym for ‘Ireland’… the mutually conflicting narratives of ‘Parable Island’, and its tone of jaded wryness, suggest a disenchantment with the endless contentiousness of Irish historiography; and this mood persists into Mud Vision (152)

- HV: In ‘Parable Island’, a poem dealing with the metaphysics of naming, the poet has taken up his habitation in a place where all appellation is contested: the natives have one name for a mountain, the occupiers another; to one school of archaeologists ‘the stone circles are pure symbol’, to another, they are ‘assembly spots or hut foundations’. There are no reliable directions in this island … (125)

- Though Heaney here takes on again the role of ‘listener’ … he himself remains unseen. Now he must listen at ground-level, be among those to whom he listens. The rights of discourse seem, alarmingly, to have passed to the untrustworthy … The importance of these poems of competing discourses lies in the poet’s conviction that the person who owns the language owns the story, and that he who wishes to change the story must first change the language (ibid125)

- whereas the archaeological discourse was deeply singular ( e.g. Tollund Man, Grauballe Man, Bog Queen – the parabolic discourse is incorrigibly plural – the subjects are ‘we’ or ‘they’. The collective is the most difficult of discourses for a modern poet, precisely because of the modern conflict between the individual and the communal. When Heaney appropriates the optatives of elder Catholics, or uses collective nouns such as ‘natives’ and ‘occupiers’, he forces his own ethnic group to hear their own linguistic usages (ibid126)

- The satirical edge that keeps showing itself in these parabolic poems suggests that all group diction becomes self-parodic over time. This is as useful a spanner to throw into the works of petrified writing and oratory as any other. It is not always by means of allegory that Heaney pursues his ethical and metaphysical questions in ‘The Haw Lantern’ (bid126)

- Heaney is a meticulous craftsman using combinations of vowel and consonant to form a poem that is something to be listened to.

- the music of the poem: fourteen assonant strands are woven into the text; Heaney places them grouped within specific areas to create internal rhymes , or reprises them at intervals or threads them through the text;

- syllables without highlight are largely the unstressed sound as in common, little [ə]

- alliterative effects allow pulses or beats, soothings or hissings or frictions of consonant sound to modify the assonant melodies; this is sonic engineering of the first order;

- a full breakdown of consonant sounds and where in the mouth they are formed is to be found in the Afterthoughts section;