‘What the Californian distance did was to lead me back into the Irish memory bank’ (DOD142).

The first poem of Wintering Out introduces a series of pieces in the collection that identify closely with beloved locations by featuring the sounds of and associations with Irish/ Ulster diction and pronunciation. Heaney refers to them as ‘languagey poems’ (DOD126).

Recalled at a restless moment and from a huge distance, Mossbawn is a sacrosanct place of Heaney’s childhood, a blessed legacy ‘ forever part of his inner landscape’ (HV 21).

The poet spotlights an age-old, traditional feed for livestock as it winters out: Fodder (required when, seasonally, grass has ceased to grow and provide renewable natural pasture); he identifies with the phonetic version he grew up with (Or, as we said, fother) and offers an emotional welcome to the returning memory: I open my arms for it again.

Heaney records and dramatizes the fodder’s provenance with visual detail familiar to him but ‘unseen’ by ordinary mortals: But first to draw from the right vise of a stack, a pulling movement that unbalanced the whole hay-rick (the weathered eaves of the stack itself falling at your feet); his smell and taste buds recall the sweet flavour of natural ingredients: last summer’s tumbled swathes of grass and meadowsweet.

This blend of natural constituents that feeds so many beasts from so little, and little short of a New Testament miracle (multiple as loaves and fishes), is distributed to livestock wintering cosily in cowsheds (a bundle tossed over half-doors) or in small enclosures: or into mucky gaps.

As he tosses and turns in his bed the unsettled, inward-looking poet longs for home: These long nights/ I would pull hay/for comfort, anything/ to bed the staII, anything to bring consolation to his Californian ‘byre’.

- fodder: dried hay and straw used as a winter feed for livestock;

- vise: local usage probably derived from Old French/Middle English words indicative of the winding, twisting method required to build and secure mown grass left in the fields;

- weathered: showing signs of long exposure to the weather;

- eaves: the section that overhangs to allow water to run off;

- tumbled: grass drying in the field s is turned over manually to hasten the process;

- swathe: mown grass lying in a long, continuous line;

- meadowsweet: tall, sweet-smelling plants that grows amongst the grass;

- multiple: numerous;

- loaves and fishes: allusion to the miracle reported in the New Testament Gospels when Jesus fed a multitude of people with five loaves and two small fishes (John’s Gospel); notion of massive riches from modest ingredients;

- bundle: armful;

- half doors: doors divided horizontally; features of farm buildings containing livestock;

- mucky: describing churned up mud and cattle manure;

- pull hay: the image is of farm machinery collecting hay from the fields;

- bed the stall: to provide a comfortable floor covering in each cowshed cubicle;

- Heaney promotes Ulster dialect and sounds as a source of common ground at a time when Northern Ireland is divided along sectarian lines: I would have thought that family and friends (both Catholic and Protestant) should have been completely at home with much of the book, since it begins with a poem about fother – not a mispronunciation of ‘father’ but the local way of saying ‘fodder’ (DOD126);

- The collection proper begins with ‘Fodder’, the first of many hymns to sacred places, objects and words which continue to quicken and nourish the poet’s imagination, at a time when human life seems no longer sacred … Recalling that single, simple word from his first home releases a spill of images, suggesting the natural and spiritual riches of Mossbawn. Aware that the age of miracles and innocence has passed, Heaney summons its memory to sustain him during the cold, bleak present. (MP94)

-

5 quartets of largely 4/5 syllables; 3 sentence structure;

- 6 punctuation marks only; copious use of enjambment reflects poet’s constant flow of consciousness;;

- title runs into the text to introduce the finger-wagging ‘Or’ of the language specialist seeking to correct the anglo-saxon pronunciation;

- variety of tense usage from preterite of habitual ‘said’ or specific description; present; conditional of habit ‘would’;

- visual description involves other sense data e.g. touch;

- Personal pronouns I/ we; poet is and has remained part of his culture; a welcome sound has been out of his mind (‘again’);

- past participles used adjectivally: weathered eaves; tumbled swathes;

- use of simile ‘multiple as loaves and fishes’ in Biblical allusion to the miraculous;

- final stanza replaces visual memory with heightened emotions, those of an exile reaffirming his cultural identity;

- indirect reference to cattle: ‘half-doors’/ ‘mucky gaps’;

-

Heaney is a meticulous craftsman using combinations of vowel and consonant to form a poem that is something to be listened to;

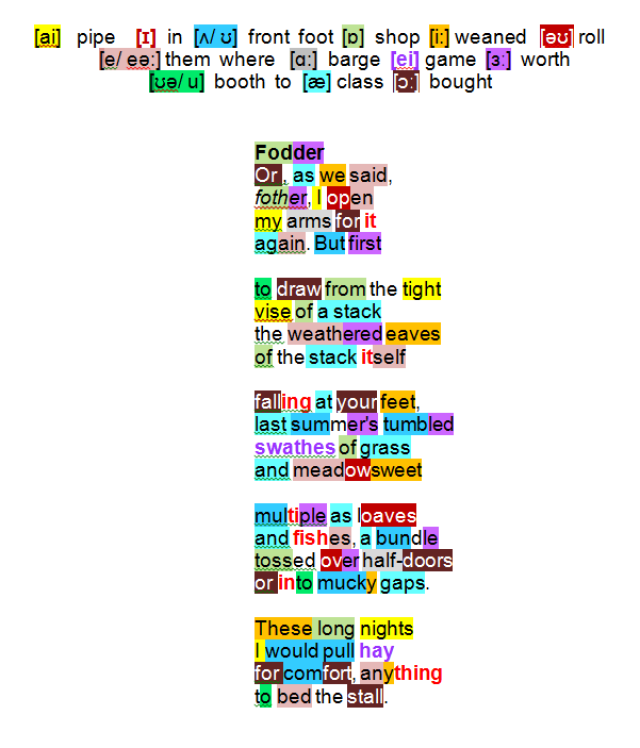

- the music of the poem: thirteen assonant strands are woven into the text; Heaney places them grouped within specific areas to create internal rhymes , or reprises them at intervals or threads them through the text.

- alliterative effects allow pulses or beats or soothings or hissings or frictions of consonant sound to modify the assonant melodies:

- the first lines of (1) for example, brings together labio-dental fricative [f] a cluster of alveolar plosives[t] interspersed with nasal [n] and [m];

- it is well worth teasing out the sound clusters for yourself to admire the poet’s sonic engineering:

- Consonants (with their phonetic symbols) can be classed according to where in the mouth they occur:

- Front-of-mouth sounds voiceless bi-labial plosive [p] voiced bi-labial plosive [b]; voiceless labio-dental fricative [f] voiced labio-dental fricative [v]; bi-labial nasal [m]; bilabial continuant [w]

- Behind-the-teeth sounds voiceless alveolar plosive [t] voiced alveolar plosive [d]; voiceless alveolar fricative as in church match [tʃ]; voiced alveolar fricative as in judge age [dʒ]; voiceless dental fricative [θ] as in thin path; voiced dental fricative as in this other [ð]; voiceless alveolar fricative [s] voiced alveolar fricative [z]; continuant [h] alveolar nasal [n] alveolar approximant [l]; alveolar trill [r]; dental ‘y’ [j] as in yet

- Rear-of-mouth sounds voiceless velar plosive [k] voiced velar plosive [g]; voiceless post-alveolar fricative [ʃ] as in ship sure, voiced post- alveolar fricative [ʒ] as in pleasure; palatal nasal [ŋ] as in ring/ anger.

to draw from the *tight* vise of a stack. There is a typo in the poem on the 5th line.

Thank you for writing this up! It has been really helpful.

Thanks Rel, I won’t be able to edit it immediately … the early’coloured hearing’ blocks need replacing! I’ll get round to them at some stage after I’ve posted ‘Haw Lantern’currently on the stocks,

warmest, David