The epigraph is quoted from Roderick Beaton’s George Seferis, Waiting for the Angel. It sets off a number of lines of interest in Heaney: how a poet appears to observers, whether his thoughtfulnesses and preoccupations are mistaken for absent-mindedness; how a poet retrieves information; the extraordinary associations that the ‘poet’ dreams up in response to objects (here Heaney responds to ‘spiky’ sharpness). One characteristic Heaney recognises he shares with Seferis is his reluctance to take political sides in public. The poem is addressed to Seferis.

Heaney portrays Seferis standing in spiky asphodel which grows wild in Greece (the same immortal flower that grew in Elysium, the abode of the blessed after death in classical antiquity), a rightly appropriate setting for a poet with Seferis’ nature. What comes to Heaney’s mind is a very different plant growing wild in Ireland: why do I think seggans?

He conjures up a particular moment in the year of the poet’s death (your days of ’71) watched by the mythological god of the sea as Seferis stood on a Greek promontory south of Athens. To Heaney the spot was rich in immediate sense data, all ozone-breeze and cavern-boom that make little impact on Seferis’ consciousness: too utterly this-worldly, George, for you.

The Greek’s mind is elsewhere, intent upon an otherworldly scene, as he struggles to assemble facts that lie in the back of a mind threatened by memory loss : just beyond/ the summit ridge, the cutting edge/ of not remembering.

He reports the Greek’s cantankerous reaction to the bright sunlight: The bloody light. To hell with it. close eyes and concentrate.

Seferis’ point de départ is based not on Jesus Christ’s suffering, a ‘good’ man condemned to his crown of thorns and crucifixion in a Herod’s court but something remembered from Plato: the hackle-spike fate rightly subjected tyrants to in Tartarus … torn to shreds in the Underworld pit of Hell by the very asphodel Seferis is standing in (a harrowing, yes, in hell, flayed with thorny aspalathoi). It appeals to Heaney’s sense of justice: as was only right for a tyrant.

For you … Heaney reflects on the reasons why the unpalatable political tyranny Seferis was experiencing in Greece, perhaps because of the way he was (maybe/ too much i’ the right, too black and white), had not yet provoked him to publish a reaction … yet there was still time: still your chance to strike against his ilk.

Heaney acknowledges the need for some ‘last straw’ triggering a public outburst deploring the current state of affairs: a last word meant to break your much contested silence. Seferis did ultimately make a ‘statement’ and became a symbol of free expression and freedom especially in the minds of young Greeks.

Heaney, aware of his own (for me) timidity as regards Irish politics during the years of sectarian chaos in Ulster weighs up (a chance to test the edge) his own ‘weaponry’ in the Irish arena (seggans, dialect blade), etymologically stronger than ‘asphodel’ – it shares its root with the word for ‘sword’ – hoar and harder and more hand-to-hand once a symbol of combativeness, replaced now by weedier approaches that lack substance (sedge – marshmallow) and come a poor second (rubber-dagger stuff).

- asphodel: a lily, its flowers borne on a spike; aspalathoi a thorny bush;

- seggans: Irish for a strong rush

- make waves: literally to cause choppy water; informally to make an impression, be disruptive;

- ozone: informal seaside smell said to be invigorating;

- utterly: used superlatively to suggest an absolute;

- summit ridge: mountainous horizon

- cutting edge: sharp edge; the latest stage of development

- bloody: adj. added to express anger, fristration

- crown of thorns: a thorny crown placed on Christ’s head prior to his crucifiction;

- sceptre: staff carried formally as a symbol of sovereignty;

- Herod: Christ’s judge

- harrow: a farm implement with sharp teeth dragged over ploughland;

- hackle spikes: akin to the teeth of a comb;

- Plato: ancient 3rd BC Greek philosopher interested in the material correspondences with abstract ideas or forms;

- bind: tie;

- fling: throw forcefully, cast headlong

- flay: strip the flesh off with a whip;

- Tartarus: place in the mythological underworld where the wicked were punished;

- tear to shreds: the result of a flaying’

- I’ the right: describing opinions or actions that are morally justified;

- black and white: aware of opposing principles

- ilk: people in the same category;

- contested: disputed;

- dialect blade; a rush strong enough to fence with;

- hoar: greyish in colour;

- hand-to-hand: at close quarters;

- sedge; a wetland grass-like plant;

- marshmallow: sugary piece of confectionery

- rubber-dagger: a non-lethal weapon routinely used in drama productions;

- 37 lines in stanzas of different lengths; lines between 4 and 10 syllables; nor formal rhyme scheme; varied punctuation and use of enjambment;

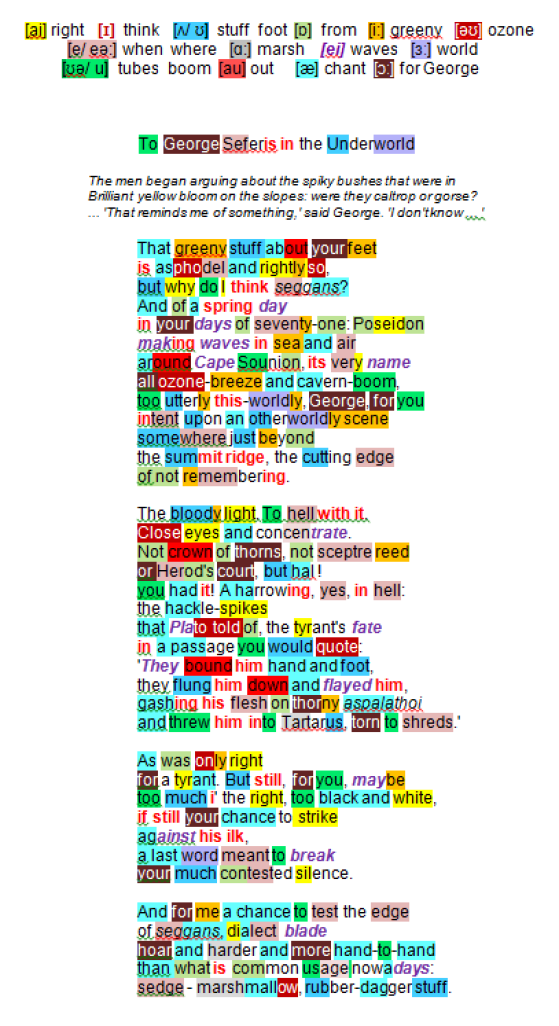

- Initial sound effects couple [i:] greeny/ feet [ai] rightly/ I with labio-dental consonant [f] stuff/ feet/ asphodel;

- stanza 2 introduces different sound flavours adding assonant [ei] day/ days/ waves/ Cape/ name and [uː] Sounion/ boom/ you/ too, [ʌ] utterly/ upon/ otherworldly/ somewhere just/ summit/ cutting to clusters of sibilant [s] and [z] consonants;

- repeated –ly;

- stanza 3: assonant [ai] of light/ eyes/ later spikes/ tyrant’s; [e] of hell/ concentrate/ sceptre/ Herod’s giving way to [æ] ha/ had A harrowing/ hackle- amidst a cluster of aspirant [h] ha/ had A harrowing/ hell/ hackle; [ei] Plato/ fate/ flayed alongside [au] bound/ down with alliterative [fl] flung/ flayed/ flesh [θ] voiceless dental fricative thorny/ aspalathoi/ threw;

- in stanza 4 assonant [ai] recurs: right/ tyrant/ right/ white/ strike/ silence interwoven with [ɪ] still/ i’/ if still/ ilk and alliterative alveolar [t];

- the final lines feature [e] test/ edge/ seggans, dialect and [ɔː] hoar/ more amongst aspirant consonant: hoar/ harder/ hand-to-hand;

- rubber-dagger: once a non-dangerous toy for children intent on play-fighting; also used in theatre to avoid injury; its use may betray Heaney’s view of his own refusal of public utterance;

- George Seferis (1900-1971): Nobel Prize winner for Literature in 1963; from Smyrna in Greece with its Homer connection; his diplomatic career took him far from home and made of him a twentieth century Odysseus, wandering, exiled and yearning for home;

- Seferis is dead; Heaney’s title is one of five in the collection that allude to death; here he uses the Greek classical reference to the Underworld . The poem’s ‘action’ would appear to take place very shortly before Seferis’s death in 1971.

- Seferis witnessed the1967 military coup in Greece following which a junta of ‘Colonels’ ruled for 7 years using a puppet government; correspondingly Heaney was caught up political turmoil surrounding the Irish ‘Troubles’.

- Seferis is reported as having been particularly opposed to ‘puppet’ Prime Minister Papadopoulos; Heaney hints that, rightly or wrongly, he and Seferis were both reluctant to take sides in public.

- There are two plants in this poem both with ‘violent’ potential: spiky Greek asphodel; the Celtic seggans, a grass which shares its root with the word for ‘sword’;

- In dialogue with Denis O’Driscoll (p388) Heaney provides insights into the provenance of this poem: I ‘was particularly fascinated by the account of what he went through during the time of the Colonels (a military junta replaced democratic government in Greece between 1967 -1974): under huge pressure to speak out against the régime, but reluctant – temperamentally and as a former diplomat – to join a chorus on the left. In the end he did issue a statement deploring the state of affairs …’

- When Heaney proclaims directly the innate, almost iconic superiority of Irish Gaelic, he can be unconvincing. In ‘To George Seferis in the Underworld’, he is dubious about overtly political poetry, but sees using the Irish word for rushes – ‘seggans’ – as a form of fighting: ‘seggans, dialect blade hoar and harder and more hand-to-hand than what is common nowadays: sedge – marshmallow, rubber-dagger stuff.’ But why? Both are derived from the root ‘to cut’ (and ‘sagja’, a sword); but the English has kept, literally, an edge in the word. Caroline Moore in The Telegraph August 2018

- Heaney is a meticulous craftsman using combinations of vowel and consonant to form a poem that is something to be listened to.

- the music of the poem: fourteen assonant strands are woven into the text; Heaney places them grouped within specific areas to create internal rhymes , or reprises them at intervals or threads them through the text:

- alliterative effects allow pulses or beats, soothings or hissings or frictions of consonant sound to modify the assonant melodies; this is sonic engineering of the first order;

- for example, the final lines bring together alveolar plosives [d] [t], sibilant variants [s] [z] , nasals [m] [n] alongside labio-dental fricatives [f] [v] and aspirate [h];

- a full breakdown of consonant sounds and where in the mouth they are formed is to be found in the Afterthoughts section;