(Inferno, Canto 111, lines 82-129)

Seamus Heaney tops and tails Seeing Things with his own versions of passages from classical masterpieces, starting with ‘The Golden Bough’ borrowed from the pre-Christian classical mythology of Virgil and ending with a Dante passage from the Christian era. In both cases the narrative is not Heaney’s as such but he employs all his compositional skills to produce a polished translation.

In conversation with DOD (p319) Heaney explained how the collection’s texts linked up: the relationship between individual poems in the different sections has some thing of the splish-splash, one-after-anotherness of stones skittering and frittering across water. Thus the collection’s themes, motifs, moods and key words pop up at intervals just as a flat stone rebounds across the water’s surface.

NC (163) In ‘The Golden Bough‘, Aeneas is told by the Sibyl how he, still living, may exceptionally penetrate hell inorder to meet the ghost of his dead father; in ‘The Crossing’ Charon, the boatman of the river Acheron, is unwilling to ferry the still living Dante across the river of hell. Virgil, however advises the poet that this is because he is not himself damned: that is, he will remain uncontaminated by his descent. Both Virgil and Dante attest, therefore, from their classical and Christian perspectives, that, if a relationship with the dead induces anxiety, nevertheless poetry is the place where such a relationship becomes possible;

From the shore where Dante, Virgil and a group of damned souls await transport across to hell a boat approaches: rowed by an aggressive (Raging and bawling) old man (hair snow-white with age), threatening perpetual desolation (‘Woe to you, wicked spirits’), providing a one-way-ticket to endless suffering (eternal darkness … fire and ice).

Used to being obeyed Charon seeks to reject Dante, the living soul, who holds a return-ticket, from the queue. Dante stands his ground; Virgil intervenes: the decision to cross was made by a higher authority (This has been willed; so there can be no question).

The terrifying boatman (wheels of fire flaming round his eyes) climbs down (straightaway he shut his grizzled jaws).

The brutishness of his manner, however, has had a dire effect on the lost souls now without dignity (all naked and exhausted) and sick with fear (Changed their colour and their teeth chattered). No one is spared their curses: neither the Creator (blasphemed God); nor their parents on the earth; nor Man in general (human race); nor the sexual act that produced them and their genetic inheritance (place and date and seedbed Of their own begetting).

Painfully (bitterly weeping) they bow to pressure and reconcile themselves to the inevitable accursed shores in the grudging acknowledgement that theirs is the fate of every man who does not fear his God.

Dante watches the ultimate humiliation at the hand of the devilish ferryman with eyes … like hot coals fanned; how he signals (beckons), bullies (herds … together) or chastises (beats with his oar).

Dante reflects on God’s Justice (the expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden) and why, as a result of Adam’s disregard for His instructions, and via him man’s innate inability to discriminate between right and wrong, sinners await transfer to hell.

Trees were predominant symbols in Eden and Dante’s simile may well derive from there: due to Adam sin is as predictable as falling leaves in autumn, applying ultimately to each and every one (until the branch is bare), God’s booty (looted) littering the floor beneath.

As a result the sinful (bad seed of Adam) submit themselves instinctively (like a falcon answering its call) to the order to proceed to hell (Pitch themselves off that shore). Scarcely have they reached hell than Dante notes the arrival of a new batch where the first queue waited.

Virgil (the courteous master) explains both Charon’s reactions to Dante and, initially, the constant flow of sinners (who die under the wrath of God): the latter are universal, impelled by the force (goads … spur) of Divine Justice that transforms their anger into enthusiasm (eager … fear ( ) turned into desire); those awaiting the ferryboat are all bad (no good spirits); Charon sensed that Dante was a good man, hence his objection.

- bawl: shout loudly and angrily;

- woe: you’ll be in trouble if you step out of line; lose hope;

- willed: pre-determined;

- grizzled jaws: unshaven stubble streaked with grey

- livid: dingy, gloomy, dark-coloured;

- chatter: click repeatedly together because of cold or fear;

- blaspheme: curse utter profanities;

- seed: Biblical reference to semen in human reproduction;

- beget: bring about reproduction;

- fan: propel air to increase strength of an open fire;

- beckon: gesture to come closer;

- herd: gather, shepherd;

- loot: steal, plunder;

- Adam: reference to the Fall of Man (Adam and Eve ejected from the Garden of Eden by God amidst suggestions that the serpent mated with Eve or even that the serpent is an allegorical reference to Adam mating with Eve against God’s wishes); some Christian Theology supposes that evil supposedly innate in all human beings was inherited from Adam in consequence of the Fall (‘original sin’ as coined by St Augustine);

- master: Virgil in conversation with Dante;

- wrath: extreme anger

- Divine Justice:constant and unchanging will of God to give everyone what is due to him or her based on their earthly existence;

- goad: provoke, prod, push onwards;

- spur: spiked instrument with which a rider urges the horse forward;

- Heaney is a meticulous craftsman using combinations of vowel and consonant to form a poem that is something to be listened to.

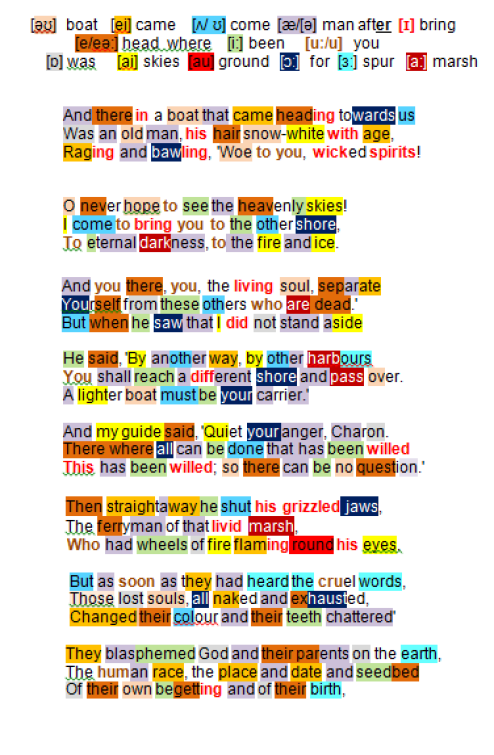

- the music of the poem: fourteen assonant strands are woven into the text; Heaney places them grouped within specific areas to create internal rhymes , or reprises them at intervals or threads them through the text:

- alliterative effects allow pulses or beats, soothings or hissings or frictions of consonant sound to modify the assonant melodies; this is sonic engineering of the first order;

- for example, the final triplet interweaves front-of-mouth sounds [w][f] [v], bi-labial plosives [p][b], sibilants [s] [z][sh] and nasal [n];

- a full breakdown of consonant sounds and where in the mouth they are formed is to be found in the Afterthoughts section;